Table of Content

- The Cognitive Cost of Unlimited Information

- Why Heuristics Improve Outcomes Rather Than Degrade Them

- Why Simpler Models Often Beat Complex Reasoning

- Practical Heuristic Frameworks That Scale Well

- Heuristics as Cognitive Load Management Tools

- Addressing the Oversimplification Critique

- When Heuristics Are Most Effective

- Final Perspective: Constraint Is Not the Enemy of Good Decisions

In technical and professional environments, decision failure rarely occurs because people lack information. It occurs because they are exposed to too much information without structure.

Across disciplines—from software architecture and clinical medicine to finance and operations research—evidence increasingly shows that bounded, rule-based decision systems outperform unconstrained analysis, especially under uncertainty.

This is not a behavioral flaw. It is a consequence of how human cognition works.

The Cognitive Cost of Unlimited Information

Human decision-making is constrained by working memory and attention. Decades of research show that once the number of active variables exceeds a small threshold, performance degrades sharply.

Key findings consistently replicated in decision-science literature:

- Decision accuracy declines once options exceed 7–9 variables

- Reaction time and error rates increase nonlinearly, not gradually

- Confidence drops even when objective decision quality remains unchanged

- Individuals begin to rely on irrelevant cues simply because they are salient

One well-known meta-analysis on choice overload found that people presented with large option sets were 20–30% less likely to make a decision at all, and significantly less satisfied when they did.

In technical decision environments, this translates into:

- Over-analysis

- Delayed execution

- Inconsistent judgments

- Retrospective regret despite “thorough” evaluation

Why Heuristics Improve Outcomes Rather Than Degrade Them

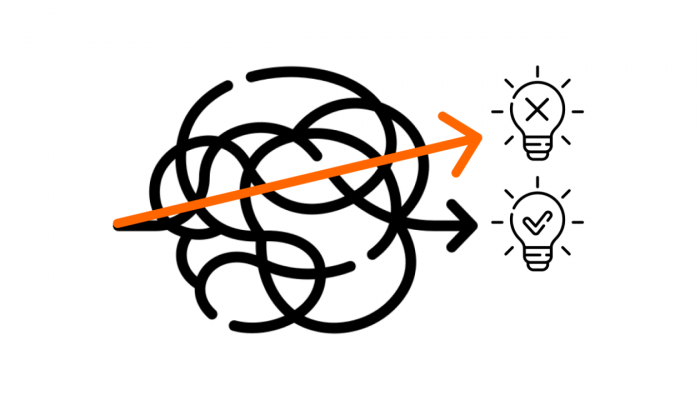

Heuristics are often mischaracterized as shortcuts that trade accuracy for speed. Empirical evidence suggests the opposite in many real-world contexts.

A heuristic is better understood as a constraint-based decision architecture.

Instead of asking:

“What can I analyze?”

It asks:

“What must I consider—and what can be safely ignored?”

This distinction matters.

When decision-makers operate within bounded frameworks:

- Cognitive load decreases

- Noise is filtered out

- Attention is directed toward high-signal variables

- Judgments become more consistent over time

In comparative studies, simple linear models using a handful of weighted criteria routinely match or outperform expert intuition, particularly in forecasting and selection tasks.

Why Simpler Models Often Beat Complex Reasoning

One counterintuitive finding in applied decision science is that model simplicity correlates with robustness.

Complex reasoning fails in practice because:

- Real-world data is noisy

- Relationships between variables are unstable

- Humans overweight recent or vivid information

- Small errors compound across many factors

Simplified frameworks resist these failure modes.

For example:

- A 5-factor weighted scoring system is easier to apply consistently than a 20-factor evaluation

- Early-elimination decision trees prevent false precision

- Binary “go / no-go” criteria outperform nuanced scoring under time pressure

This is why high-stakes systems—aviation safety, surgical protocols, nuclear operations—rely on checklists and rule hierarchies rather than discretionary judgment.

Practical Heuristic Frameworks That Scale Well

1. Constrained Criteria Evaluation

Limiting decision criteria forces prioritization. When teams are restricted to a small number of evaluation dimensions, discussions shift from preference to impact.

Observed effects:

- Reduced meeting time

- Higher alignment across evaluators

- Fewer post-decision reversals

The constraint is the feature, not the limitation.

2. Early-Elimination Decision Trees

Decision trees that eliminate options early prevent cognitive dilution.

Instead of comparing everything against everything else, they ask:

- Does this meet the minimum threshold?

- If not, discard it immediately

This mirrors how experienced engineers, clinicians, and investors actually think—by ruling out failure conditions first.

3. Weighted Scoring Over Raw Metrics

Raw numbers invite false objectivity. Weighting forces explicit trade-offs.

A properly designed scoring framework:

- Acknowledges unequal importance

- Prevents minor metrics from dominating outcomes

- Makes reasoning transparent and reviewable

The goal is not mathematical precision—it is decision coherence.

Heuristics as Cognitive Load Management Tools

Cognitive load is not an abstract concept. It directly correlates with error rates.

Under high load:

- People default to pattern-matching

- Biases intensify

- Confidence becomes decoupled from accuracy

Heuristics function as load-shedding mechanisms.

They:

- Reduce working-memory requirements

- Externalize reasoning into structure

- Allow focus on judgment rather than computation

This is why experienced professionals appear “intuitive”—their intuition is often the result of internalized heuristics built over time.

Addressing the Oversimplification Critique

The common objection is that heuristics oversimplify complex reality.

In practice, unstructured reasoning oversimplifies far more aggressively, because it relies on:

- Salient anecdotes

- Emotional weighting

- Inconsistent criteria

- Post-hoc rationalization

Heuristics do not deny complexity. They manage it explicitly.

They make assumptions visible, testable, and improvable—something intuition rarely allows.

When Heuristics Are Most Effective

Heuristics work best when:

- Decisions are repeated

- Conditions are uncertain

- Time or attention is limited

- Absolute optimality is unknowable

They are less suitable for:

- One-off, deeply novel problems

- Situations with complete, stable data

- Domains requiring exhaustive proof

Knowing when not to use heuristics is part of expert judgment.

Final Perspective: Constraint Is Not the Enemy of Good Decisions

The highest-quality decisions are rarely the most comprehensive ones. They are the most well-constrained.

Heuristics and simplified frameworks:

- Reduce noise

- Preserve signal

- Improve consistency

- Enable action without regret

In environments saturated with data, structured limitation is a form of expertise, not a compromise.

Post Comments

Be the first to post comment!